For complete beginners!

Writing interactive fiction has never been easier – there are so many authoring systems available. Twine has become especially popular for web-based IF because of its user friendly approach, using visual tools to allow you plan your story with “sticky notes and string”.

Ink by comparison, is a system that wasn’t originally designed for the web. It was designed as a pluggable component that integrates into a traditional game engine. At inkle, we’ve used it for almost everything we’ve created, from 80 Days (initially for mobile) to the upcoming Heaven’s Vault for PS4 and PC. Since we open sourced it, it’s also been used in a host of highly respected indie games including Bury Me My Love and Where the Water Tastes Like Wine, both nominated for IGFs in 2018.

But it’s easy to write stories for the web in ink! What’s been lacking until now is a straightforward tutorial that demonstrates the basics of writing a story in ink, exporting it for web, and making it available for others to play.

This guide will assume zero prior knowledge of ink or web technology, so that less technical writers have everything they need to get started, but we’ll provide jumping off points throughout if you want to learn more about a topic in depth.

Here’s the rough structure that we’ll follow. Feel free to skip or skim over any topics that you are already familiar with.

- Getting started with ink: downloading the tools and writing a simple branching narrative.

- Exporting for web – how to create a shareable web page of your story

- Optional: Customising the look and feel of the page, including an explanation of the basics of CSS.

- Uploading to itch.io: the perfect place to upload your work for others to play.

Getting started with ink

There’s an official manual for writing in ink that tells you everything you would need to know, from the basics to the complex and powerful structures.

But this guide will jump through all that, pointing out only the most easily-understood features that will allow you to write a simple Choose Your Own Adventure style structure. At any point though, feel free to jump into the official guide if you want to try something more advanced.

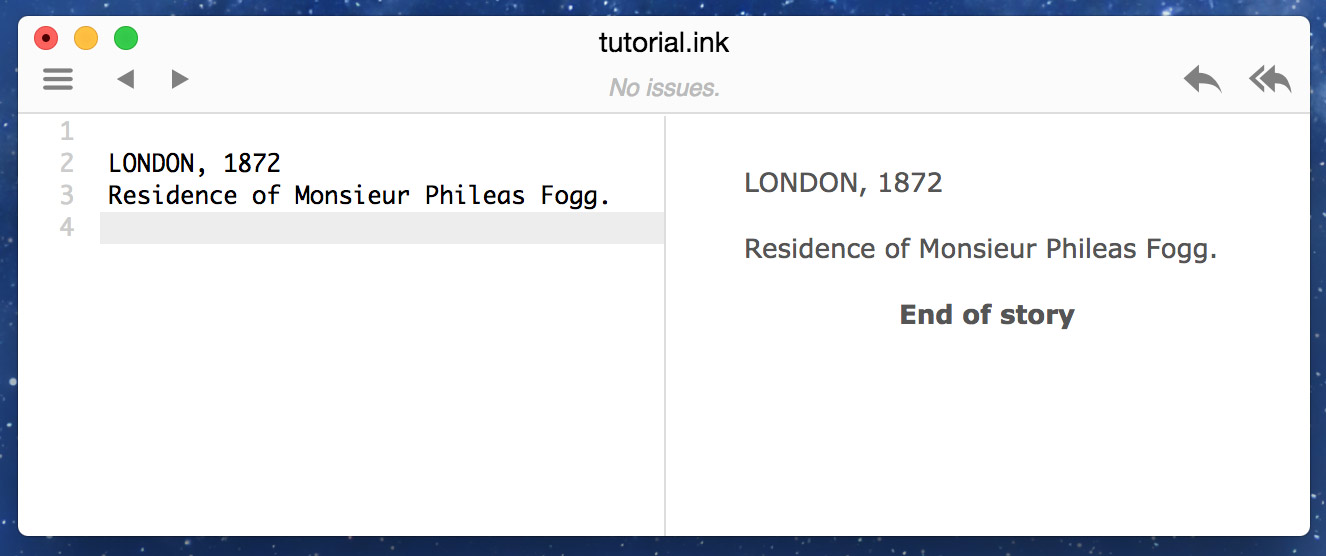

We’ll be writing in Inky – the official editor for authoring ink scripts. So, go ahead and click here to download it!

When you launch it, you’ll see a window with two columns. On the left hand side is where you write your script, and on the right hand side is where you’ll be able to play a preview of it.

The first thing to know about ink is that fundamentally, it’s just pure written text, with special annotations (“markup”) that make it interactive. So go ahead – write a sentence on the left hand side, and you’ll see it appear on the play area on the right. Adding multiple paragraphs works just fine too.

The anatomy of an ink story

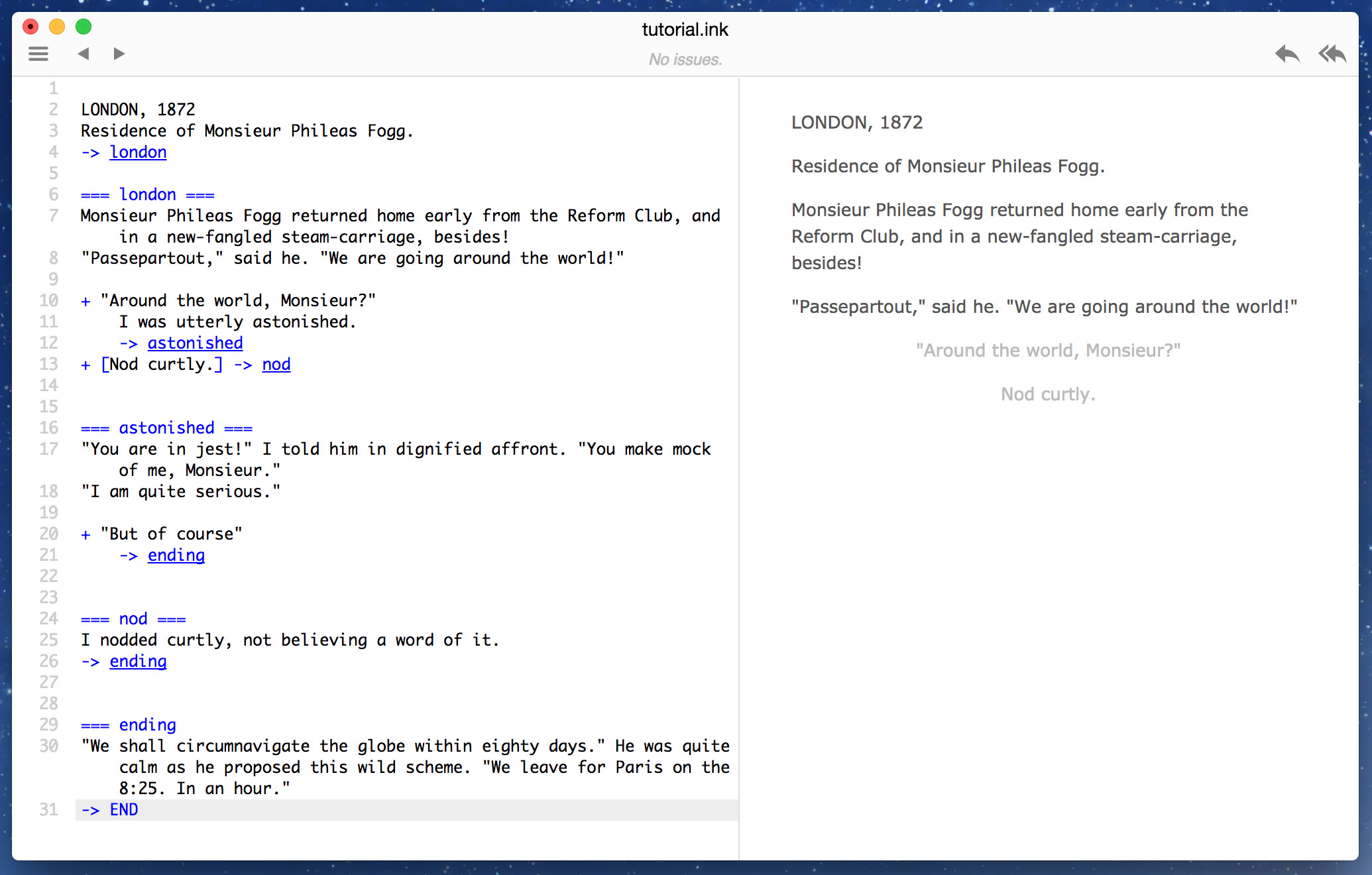

Now, let’s jump straight in and take a look at a simple example of a branching story.

The blue markup in the screenshot below might look initially intimidating if you’ve never done any programming before (lots of symbols!), but we’ll go through it bit by bit so you can understand how it fits together.

For the full text of the story, click here.

Feel free to copy and paste this directly into the left hand pane of Inky, and then play through it in the right-hand pane. To reset the story back to the beginning, press the double arrow at the top right (the other arrow rewinds a single choice).

While you’re playing, you can simply tweak the text on the left, and it’ll update live in the preview, even if you’re in the middle of the story. You can even alt-click a word on the right hand pane and it’ll select the source text on the left hand pane (this is extremely useful when a story gets quite complex!)

There are just three anatomical parts you have to understand in this simple story: knots, diverts and choices.

1. KNOTS

The story is comprised of multiple linked sections which we call “knots” in ink terminology. The start of a knot is indicated in ink using at least two equals signs the left hand side knot’s name, and optionally on the right too (so for example === london ===). The blue highlighting in Inky indicates ink markup that has recognised, confirming to us that it’s been written correctly, and making it stand out as being separate to our content.

All the content below a knot header then belongs to that knot.

The knot’s name (which can’t have any spaces in it) won’t appear in the story itself; instead it’s used when we want to link sections of our interactive narrative together.

2. DIVERTS

Now, talking of linking, this bit is called a divert:

-> london

Using the divert arrow (entered as “minus” then “arrow bracket”), we tell the story to go to a different knot. When the story is played, the join will be automatic and invisible to the player.

So, at the very beginning of our story, after showing the introductory paragraph, we have the -> london divert which takes the player directly into the knot with that name.

There’s also a special kind of divert at the end of this story. If you divert to “END”, that simply tells ink we’re done; this ending is intentional. Try removing the line with -> END on it: Inky will show a warning icon in the margin. If you mouse over the warning, it’ll tell you that you have a “loose end”.

This is an important feature of ink, and one which will help you as you story becomes increasingly complex. As you diverge your story in different directions, you’ll realise that as you write, you have to leave divergent threads of your story unfinished. These warnings remain as reminders of which parts you still have left to write.

3. CHOICES

Talking of divergence, the final crucial feature that we need in order to become dangerous with interactive writing is of course, choices:

+ "Around the world, Monsieur?"

Choices in ink are designed to look like a series of bullet points. Frequently, they’re directly combined with diverts in order to create a choice that directly takes you elsewhere in the story:

+ [Nod curtly.] -> nod

There are a few things to note about the way we’ve authored these ones.

Normally, the text you put in your choice becomes both the text of the clickable choice, as well as text that appears in the main body after you click it. However, if you want a “silent” choice, with text that only appears on the choice itself, you can put the text in [square brackets ], as you can see with the second example.

This can be used stylistically, and is often used for the difference between a command-like choice and a choice that sounds narrated, as part of the story. For example:

+ [Nod curtly.] -> nod

+ I nodded curtly. -> nod

== nod ==

It seemed unbelievable.

The first choice would only produce the It seemed unbelievable. text after picking the choice, whereas the second would produce I nodded curtly. It seemed unbelievable..

You can also add extra lines of text under the choice. This will be used as content to be shown after the choice has been taken, and not before. For example:

+ "Around the world, Monsieur?"

I was utterly astonished.

"You are in jest!" I told him in dignified affront.

-> astonished

=== astonished ===

...etc...

… is equivalent to:

+ "Around the world, Monsieur?" -> astonished

=== astonished ===

I was utterly astonished.

"You are in jest!" I told him in dignified affront.

...etc...

ink is very flexible – it allows you lots of different ways to structure your narrative.

And a final note about the overall structure of an ink story: the ink will always begin at the top of the file, and work its way down. But if all of your content is split into knots, it’s important to make sure that at the very least you have an initial divert at the top of the file (such as -> intro) to tell it which knot to begin with.

Now, why not experiment with this story? Try inserting extra text, extra choices, extra diverts, extra endings, and see what happens! As an exercise to get started – perhaps try and turn the introductory paragraph into its own knot?

If you like: Conditional content

So far, everything we’ve written could’ve been authored as a printed Choose Your Own Adventure type novel. But what if we want to show different text and choices depending on what the player did in the past?

The ink engine takes note of every section of content that the player reads, so that you can query this later on. For example, to determine whether the player saw a particular knot called catacombs:

{ catacombs:

It was darker here than the Paris catacombs.

}

Within one of these curly-brace sections you can include multiple lines of content. You can also include diverts and choices in them.

However, a more succinct way of writing conditional choices is the following, which is the neatest way to provide a specific choice only if a particular knot has been seen:

+ {catacombs} [Tell her what you found] -> tell_her

If you want to invert the condition – in other words if you want to check if they player didn’t visit the catacombs, you can simply prepend it with not:

+ {not catacombs} [Visit the catacombs] -> catacombs

Finally, you can use and and or to form more complex conditions, and you can use parentheses to clarify the specifics of the logic. A couple of examples:

{ catacombs and not pick_up_ring:

"So you didn't find it then?" she enquired.

+ [Apologise.] -> apologise

}

{ (catacombs or cross_river or sing_in_rain) and not buy_new_shoes:

My shoes were sodden from earlier in the day.

}

Advanced ink

We’ve only looked at a fraction of the powerful features that are available in ink. If you want to read more about it or just dive more deeply into something we’ve already seen, check out the official documentation. To give you a taste:

- As with any programming language, you can create custom variables, and perform mathematical calculations.

- We’ve been using

+as choice bullets, whereas normally we would recommend using*. The difference is that a*choice will never reappear once it’s been chosen – great for repeated hubs of content where you don’t want the player to read a specific section repeatedly. - There’s a harder-to-learn but easier-to-write system for writing intricate branches called “weave” that doesn’t require you to name every section with its own header. Most of our game 80 Days was written this way.

- Within knots you can also have sub-sections called “stitches”.

- Writing content that varies and branches mid-sentence is both possible and straightforward.

- You can split up your ink file into smaller ones that are linked together.

- And much much more!

Exporting for web

The next step is to save our story out to a set of files that can be uploaded somewhere as a webpage. To do this from Inky, choose File, then “Export for web…”, and choose the name of your story. The name you choose will be used both for the visible title on the webpage (so use spaces and proper capitalisation!), as well as the name of the folder that it gets saved into.

As you make changes to the story, and especially if you decide to make changes to the look and feel (see below), then in future you should choose the “Export story.js only…” option, saving it into the same folder and overwriting “yourStoryName.js”. This is the only file that needs to be updated as you change your ink content – the rest is purely part of the web template. So, if you change the look and feel of the template, you don’t want to accidentally overwrite it.

At this point, you’re already done! You can skip to the Upload to itch.io step, if you like.

However, if you’d like to add images, set a byline, use a dark theme, or have a play with the look and feel of your story, read on!

Special features for the web

ink has been designed to be as focussed as possible on one task: writing interactive text. We’ve resisted overloading the language with extra features in order to keep a good balance of power, flexibility and simplicity.

So, ink-the-language doesn’t have any built-in tools for things such as inserting images, since it’s totally dependent on the type of story you’re making. If you were writing dialogue for a 3D game, specifying an image to be displayed wouldn’t necessarily make sense.

However, Inky does provide some extra features that can be used specifically when saving for the web (since version 0.10.0). These extra features all use ink’s tag system, which allows you to provide special text annotations to each line, either before it or above. The tags are just pure text that’s invisible to the reader, but can be read by the game system, or in our case, the web template.

Images

Here’s how you insert an image:

# IMAGE: imageName.jpg

The image file should be in the same folder as your other files, or if you want you can use a path such as:

# IMAGE: myImages/imageName.jpg

You can also add an image tag on the end of the line. The image will always be shown above the text in the game.

The above picture is a dog. # IMAGE: dog.jpg

(This is actually because all tags are associated with particular lines of text, and when you have a tag on a line on its own, it’ll be associated with the line of text below it.)

Clearing the screen

Another feature that’s specific to Inky’s web template is the clear tag:

# CLEAR

This will remove all the text in the current flow, and start again from the top of the page. Make sure you only insert this directly after a choice! If you insert it in the middle of a section of text, the top part will be cleared before it’s seen.

Global tags: dark theme and author

To use the dark theme, simply put this at the very top of your ink file:

# theme: dark

The web template is able to read this in as a global tag, and has built in styling to change theme. (It uses “dark” as a class for the overall page. When you see uses of the .dark selector in the CSS file, these are the dark theme specific overrides.)

To set the author name, put this at the top of your ink file:

# author: Your Name

This will be found by the inky web template and used to insert a byline directly below the main title.

Custom CSS classes

You can also fully customise the appearance of individual lines of text using CSS classes. In your ink, add a tag to a line like this:

You make your way into the forest.

There's a pool of blood on the ground. # CLASS: danger

You can then tell the browser what the “danger” class looks like by adding the following to your style.css:

.danger {

color: red;

}

The dot followed by a word is how we define a style class in CSS. Most of our previous examples didn’t have dots since they were built in elements such as “p” for “paragraph”. These can also be combined, so p.danger would mean “a paragraph with the danger class”, and would work just as well in our example.

Custom CSS Example: The End

The Inky template contains built in styling for a class called end, if you want to show the words The End in a centred/bold style. So, to use it, put the following at the end of your story:

# CLASS: end

The End

-> END

To recap:

- The middle line is the text itself.

- The first line applies the CSS class “end” to the text.

- The last line tells the ink engine that we’re intentionally finished, it’s not a loose end.

And to tweak the styling of the end CSS class, look for .end at the bottom of the CSS file.

Restarting the story

The Inky web template has one more built in feature. If you insert a # RESTART tag, it will immediately clear the story’s progress (including all history of the player’s choices and all variables) and start again from the beginning. Since it’s immediate, you’ll probably want to put it behind a choice, like this:

You died!

+ Try again from the beginning.

# RESTART

-> END

The -> END divert will never actually be reached, but it’s good practice: you will still want to have it there to prevent Inky from complaining that you have a loose end.

Customising the look and feel

This guide is targetted at complete beginners – it assumes no knowledge of web technology.

The above export step should’ve saved out a folder with the following files:

- index.html – the HTML file is the one that binds the others together, and is the main one that you double click if you want to view your story. It tells the browser the rough structure of the page, and tells it to load the other files.

- main.js – this is the main JavaScript file where you can customise the behaviour of the way the story is presented.

- style.css – this is the main CSS file, which determines things like colours, fonts as well as sizing and spacing information such as the widths of paragraphs and the margins. We can also define transitions, such as the way the paragraphs fade in.

- yourStoryName.js – this is your actual ink content, as exported by Inky. This is the only file that’s fully unique to your story, as opposed to part of a generic template saved out by Inky. You should never edit this file directly.

- ink.js – This is the JavaScript port of the ink engine itself.

To change any of these files, you should open them up in a pure text editor. We recommend Sublime Text, but you could also use Notepad++ on Windows, TextEdit on Mac, or any other editor you’re familiar with. However, do not use Microsoft Word!

How to change fonts and colours

Fonts and colours are all controlled from the CSS file – style.css. If you open up the file, you’ll see a series of blocks like this one:

body {

font-family: 'Open Sans', sans-serif;

font-weight: lighter;

background: white;

}

Each one starts with a name like “body” or “h1”. In CSS this is called a selector since it selects a particular part of the webpage for styling. In the above case it selects the body, which is effectively the entire page.

The list of fonts following font-family is in priority order; it depends on what’s available on the user’s computer. In the above example Open Sans is a web font that’s imported at the top of the file – just visit fonts.google.com for a selection to choose from, and instructions on how to use them (it gives you one of those @import lines you can paste in yourself). If for some reason this font can’t be downloaded, it’ll fall back to the sans-serif option.

You can also use a font that’s built into the user’s system, but the problem is that there’s a very limited selection that are guaranteed to exist. The very most basic fallbacks can be specified using simply serif and sans-serif.

A few of the CSS selectors and rules in the file include:

h1– this stands for “header level 1” – i.e. the largest header, which is used for the main title of the story at the top of the page. If you wanted change the size of the title, you could change thefont-sizeproperty in here. Similarly theh1, h2is a shortcut for setting rules on two selectors at once – header levels 1 and 2. The later is used for the byline if you have an# author: Your Nametag at the top of your ink..header– A name preceeded by a dot is a class name. This particular example selects an element that’s simply a container for the title and byline. Often in HTML/CSS, elements are given containers to help with structuring or to give fine control over spacing and layout.p– this stands for “paragraph”. It’s the selector for the main body text on the page. So this is where you should look if you want to change the font size, text colour, etc.a– This stands for anchor tag, which is HTML terminology for clickable link – these are mostly just used on our page for clickable choices, but could be anything.p.choice– This translates to “a paragraph with the ‘choice’ class”. If it was just.choice, it would mean “anything with a choice class”. Choices on our page are actually structured as specially styled paragraphs that contain clickable links (anchor tags).a:hover– Here,:hoveris called a pseudo-class, and it’s used to select an element when the user has their mouse pointer over it.

CSS applies styles according to priorities that are based on how specific the selector is (more specific is higher priority) and position in the file (lower down is higher priority). This allows you to define styles initially with broad strokes and then progressively override them. For example, we define h2 first, then lower down .dark h2 overrides part of h2’s style: we change the colouring when the dark theme is active (when the .dark class is given to the whole page – ).

For more on all the different ways you can change the styling using CSS alone, try googling “CSS tutorial” – there are loads of great resources out there!

Here’s a couple of tutorials to get started:

- CSS tutorial on w3schools.com

- HTML tutorial on w3schools.com – the HTML file describes the structure of the page, so if you want to change the overall layout and customise it further, you should learn both HTML and CSS together – they go hand in hand.

Example: Big fancy title

Select a font on Google Fonts, and insert the @import line at the top of your CSS file, such as:

@import url('https://fonts.googleapis.com/css?family=Lobster');

Then change your header rule to something like:

h1 {

font-family: 'Lobster', cursive;

font-size: 80pt;

text-align: center;

}

Upload to itch.io

You’ve finished your masterpiece! Time to share it with the world.

You could choose to upload your files anywhere that allows you to host a webpage, but we’re suggesting itch.io because it has a great community of indie game creators, it’s one of the few places that allow you to upload pure web content, and best of all, it’s free! You can even choose to sell your content, if you like.

itch.io also lets you upload a private draft of your game content so you can test out the process before you release it.

Finally, ink jam is hosted from itch.io, making it trivial to enter if you’ve already got your game uploaded on the platform.

First of all, register for an account here if you haven’t already. Then:

- From dashboard choose Create New Project.

- Enter the details of your game/story, making sure to choose “HTML” for type of project.

- Zip up all the files exported from inky and upload them.

- Choose “This file will be played in the browser”.

- Embed: We suggest you experiment with this setting to see what you prefer.

- Size: We suggest 800 x 600 is better for reading text than default size. It’ll still downsize okay for mobile.

- Mobile friendly: yes

- Automatically start: We suggest you play with it and decide what you prefer.

- Full screen button: We suggest yes, but it’s up to you.

- Enable scrollbars: This isn’t necessary since the template has scrolling built in.

You can view a preview of your game on itch.io all the while you have Draft selected under Visibility & access. As soon as you’re ready to put the game live, simply select public.